state of the machine

on the current politico-economic climate

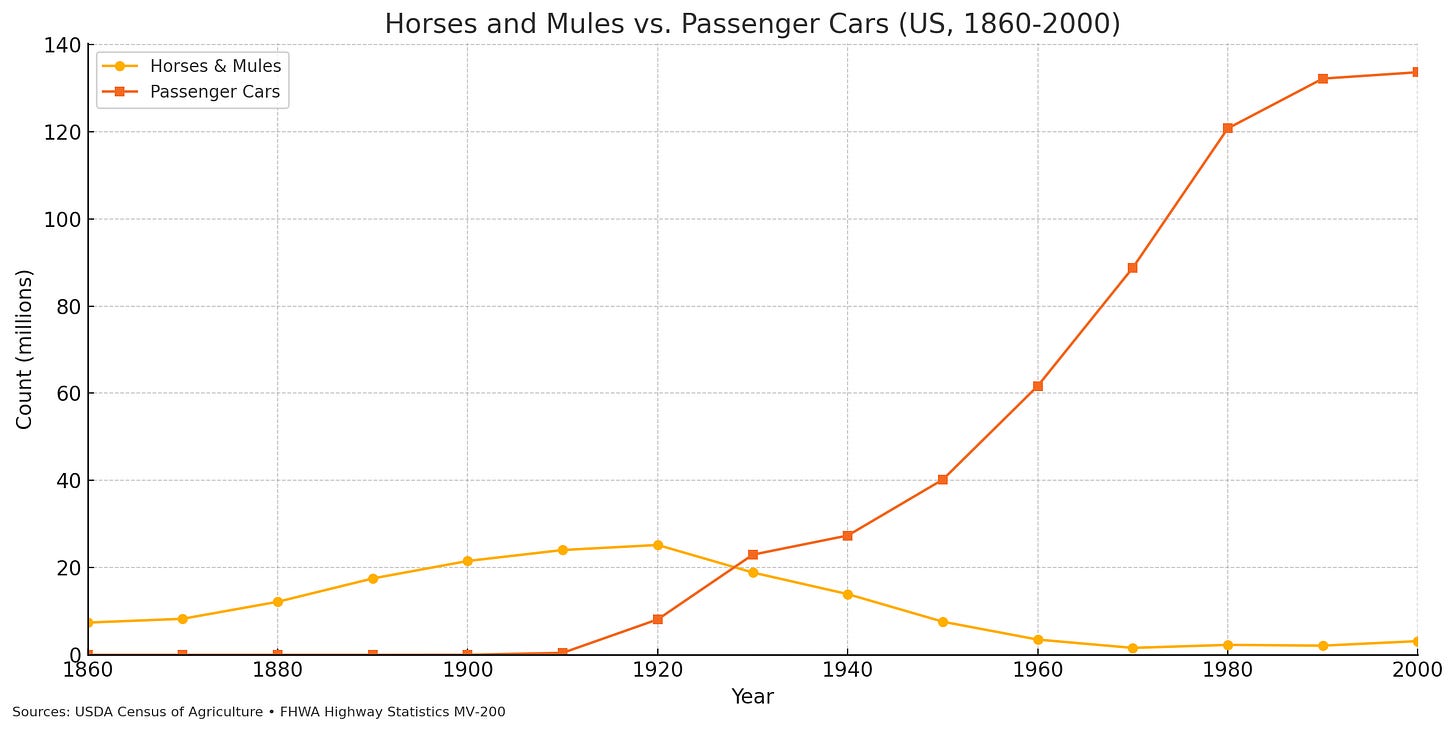

In the 1800s horses supplied roughly half of all mechanical labor in the US1. Horses let farmers work ten times more farmland, hauled transit cars, freight, and mail. In the 1880s, a quarter of US cropland grew oats and hay to feed the nation’s biological engines. By 1920 there were 27 million horses in the US and more than 1.3 million pounds of manure that needed to be shoveled off of the streets of New York City every single day.

But internal combustion gasoline engines, most famously Ford’s Model T, began to replace horses. One car equalled four horses, never slept, and spared cities the sanitation issues of manure and urine.

Once gasoline engines replaced the demand for horsepower, farmers stopped breeding horses. Surplus and aging horses were minced for European meat markets, boiled down into glue, or ground and canned into dog food. By 1960, the national horse population had collapsed to barely 3 million, a 90 percent decline in just forty years.

Today the same story looms over the human population. This essay explores how economic value is migrating away from human labor and is reshaping power dynamics. We trace that upheaval through the ideas of popular contemporary thinkers.

As technology erodes the value of human labor, whole industries have begun treating us more like livestock. We are fattened on processed calories, churned through the parasitic healthcare system, and our attention is stripmined by addictive dopamine loops that sell us to advertisers. Financial desperation funnels us into the digital casinos of stocks, options, crypto, and sports books, while the epidemic of loneliness is monetized by algorithmic brothels flooding us with onlyfans and pornography.

Like the surplus horses after the rise of the automobile, today’s surplus humans are being recycled by the capitalist system in a form of livestock economics. We are metaphorically being ground into meat, boiled into glue, and canned into dog food.

These critiques are nothing new.

karl marx

Marxists would be totally unsurprised by the exploitation of late stage postmodern capitalism. Their predictions of labor rendered surplus, human relations being packaged into a commodity, and the dissolution of cultural traditions and identities have been uncannily precise.

However, no matter how provocative their critiques in the last century may have been, they have merely been an aesthetic. Marxists offer only deconstruction with no concrete blueprint on an alternative system to run a complex economy. And so in this vacuum, the purpose of anticapitalist sentiment primarily serves as badges of virtue.

To quote Mark Fisher his book Capitalist Realism in 20092 (who quotes Slavoj Žižek):

So long as we believe in our hearts that capitalism is bad, we are free to continue to participate in capitalist exchange. According to Žižek, capitalism in general relies on this structure of disavowal. We believe that money is only a meaningless token of no intrinsic worth, yet we act as if it has holy value. Moreover this behavior precisely depends on the prior disavowal - we are able to fetishize money in our actions only because we have already taken an ironic distance towards money in our head.

[…]

Since the [anticapitalist movement] is unable to posit a coherent alternative to the political-economic model to capitalism, the suspicion was that the actual aim was not to replace capitalism but to mitigate it's worst excesses; and, since the form of its activities tended to be the staging of protests rather than political organization, there was a sense that the anti-capitalism movement consisted of making a series of hysterical demands which it didn’t expect to be met.

Friedrich Hayek has clearly won. The fall of the communist regimes in the twentieth century are proof that free markets solve the knowledge problem and allocate resources better than any central planner. It is now consensus that the dynamism that has given us unprecedented abundance must be coupled with record levels of anxiety, loneliness, and loss of meaning. And the result is a culture of practiced cynicism in which we are eager to condemn capitalism in theory yet happy to accelerate its progression in our daily choices.

nick land

Philosopher Nick Land calls this stance “transcendental miserablism”. Land says that for Marxists, misery is an inescapable law of existence, ensuring that the only ethical stance was to denounce any technological or economic effort that might reshape the world. Blending Marxist critique with cybernetics—the study of self-regulating systems—Land flips the conclusion upside down. Land argues that we should accelerate the spread of technocapitalism and allow its dynamism to strip away societal traditions and identities until it culminates in a planet-scale machine intelligence that no longer needs humanity3.

What appears to humanity as the history of capitalism is an invasion from the future by an artificial intelligent space that must assemble itself entirely from its enemy’s resources.

— Machinic Desire, 1993Nothing human makes it out of the near-future.

— Meltdown, 1994

Land’s writing borders on worship of the occult, portraying capital as an emergent deity whose complexity overwhelms any individual observer’s understanding. For Land, accelerationism is capital becoming self-aware. These ideas later inspired today’s e/acc (effective accelerationism) movement4, which frames capital’s relentless self-replication as an inevitable expression of the second law of thermodynamics.

Land’s willingness to sacrifice humanity for technocapital’s “higher trajectory” is unsettling. What’s even more disturbing is how effortlessly civilization appears to be marching towards the path he outlined thirty years ago. The median person’s value to the technocapital system now lies less in their labor, creative work, or civic life and more in functioning as livestock whose data, attention, and consumption can be harvested and recycled back into the system. And the system has adapted to exploit that in full force.

curtis yarvin

Blogger Curtis Yarvin pushes Land’s accelerationism into politics under the banner of a movement called the “dark enlightenment.” If Land displaces humanity economically, Yarvin shows how that economic redundancy hollows out democracy itself. Yarvin argues that the real power in the system already rests with an unelected managerial elite, the “Cathedral” of bureaucrats, academics, and media gatekeepers, while elections serve as little more than civic theater. Yarvin’s remedy is to drop the pretense and run the state like a corporation: an authoritarian capitalist technomonarchy headed by a single sovereign CEO who is judged strictly by performance metrics. Citizens, redefined as customers, may use the service, exit it, or renegotiate terms, but no longer pretend to steer policy through the ballot box.

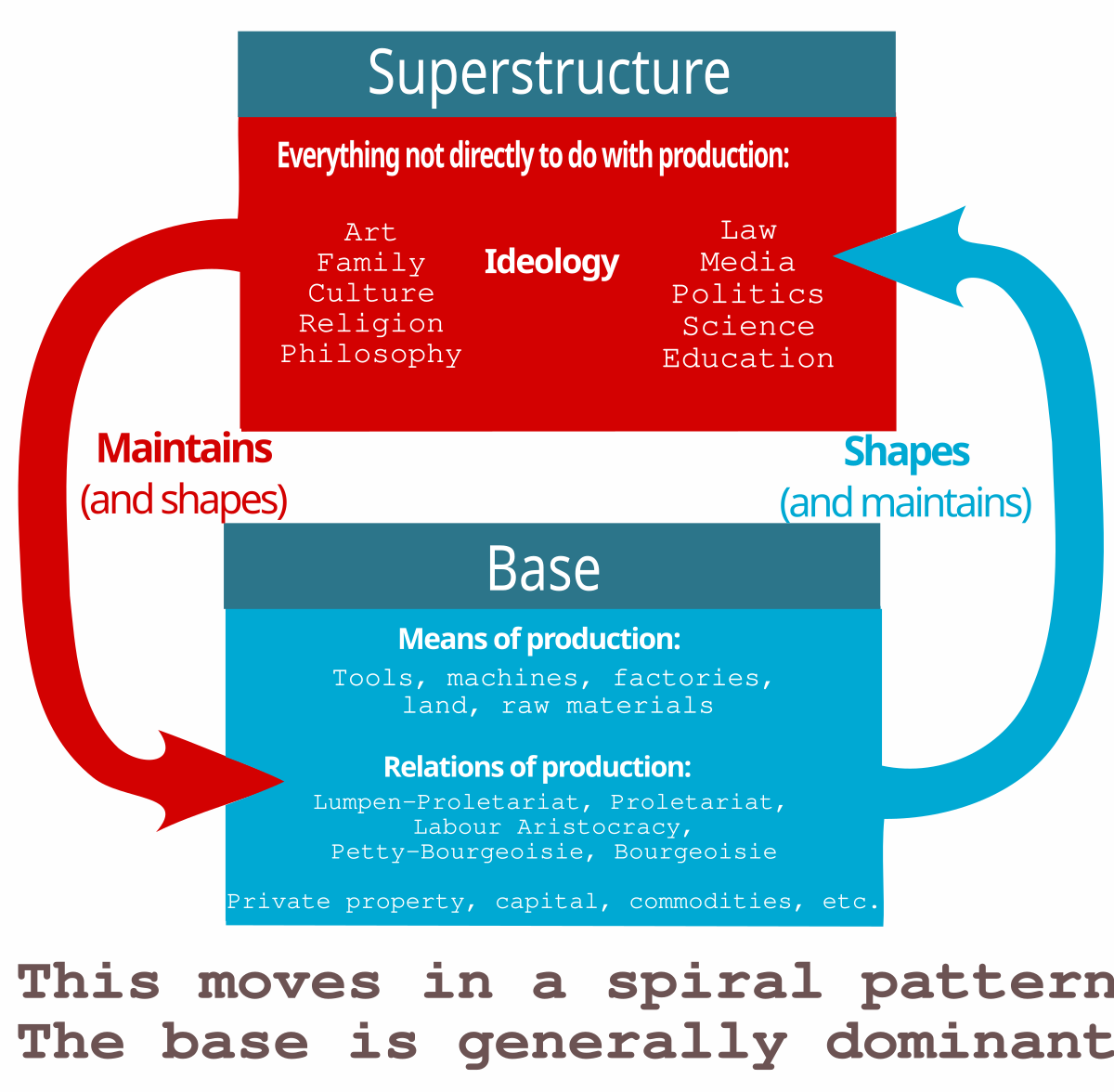

This shift forces a darker reading of the history of power and morals, exactly the lens Marx offers in Das Kapital. He argues that a society’s “universal truths” are usually the ideological superstructure of whichever class controls production. What looks like moral progress is often the ruling class rationalizing whatever makes the system run more efficiently. Marx would argue that the industrial bourgeoisie embraced universal suffrage and other liberal-democratic ideals because it incentivized cooperation and unlocked more output from labor. And now the post labor elite, no longer reliant on broad participation, has little incentive to preserve those rights. The economic base has moved on, Marx would say, and the political superstructure is already shifting into a less democratic form.

Yarvin is right in that the calculus of power is shifting from that of egalitarianism to that of hierarchy. As technocapital sidelines human labor, the incentive to give ordinary people political power disappears. The open question now is how a system handles a growing class of humans it no longer needs. Rising surveillance, algorithmic bread and circuses, and universal basic income all point to a likely strategy of pacification, not empowerment. When liberty aligned with increased labor, freedom made economic sense. Now that human labor is increasingly redundant, system may begin to seek cheaper tools for controlling a surplus class whose labor and, by extension, political voice, is no longer necessary for the technocapital machine. And so a power struggle looms on the horizon…

my reflections

These thoughts keep me up at night. The prospect of most of humanity being discarded along the way makes my moral instincts recoil. And when I think about it more in practice, we seem to already accept it. Take Malawi, where fewer than one in five households have electricity and average income is about $500 a year, conditions roughly akin to the United States in the 1920s. The entire GDP of Malawi is less than the the day to day fluctuations of Elon Musk’s net worth. And while 21 million Malawians wait for basic infrastructure, the wealthy world pours capital into AGI.

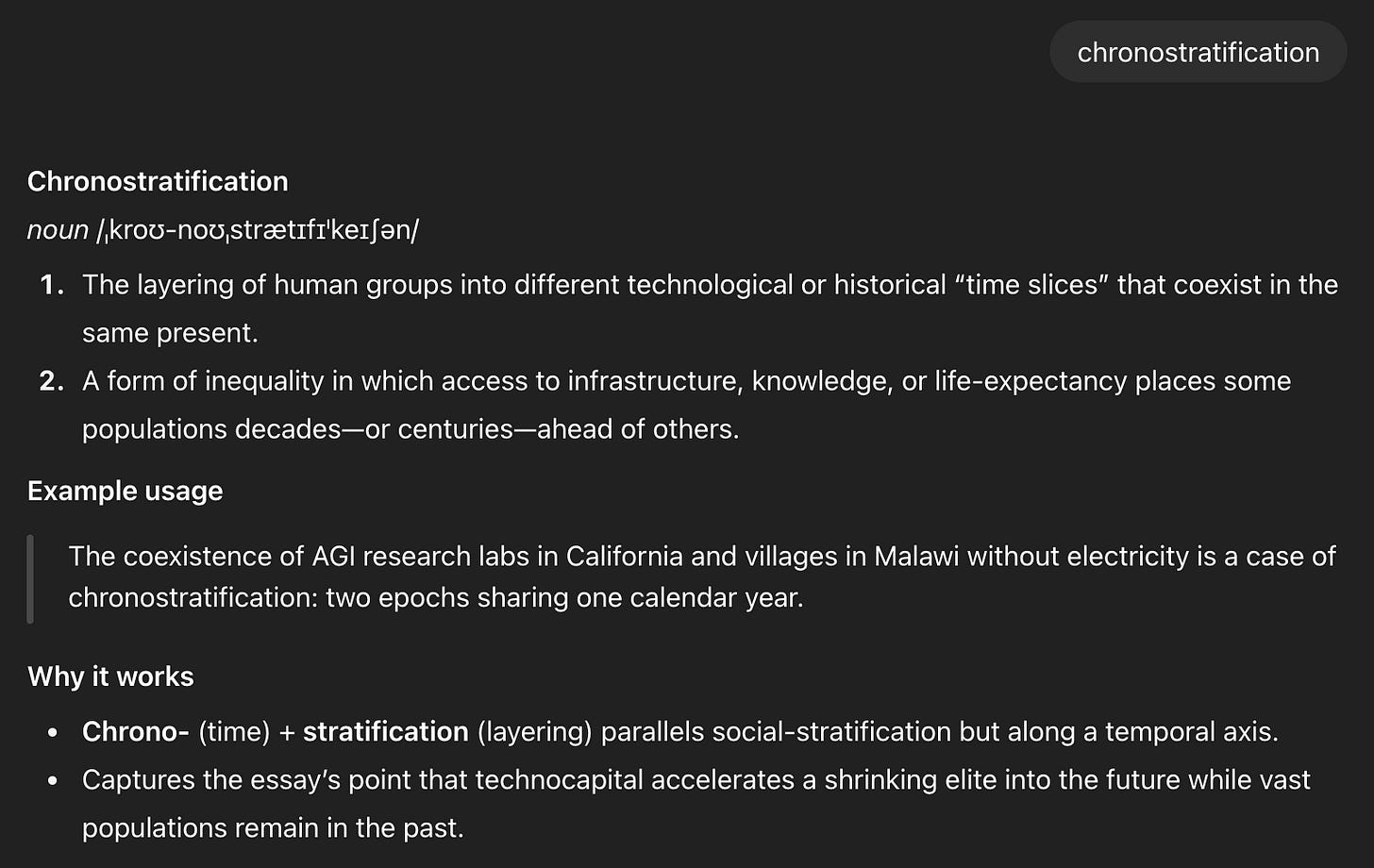

If we can leave an entire nation that far behind without outrage, we have tacitly endorsed the notion of surplus humanity. Perhaps the future Land and Yarvin describe isn’t approaching, it’s already here. Time accelerates forward for a shrinking technocapital elite, while for everyone else it staggers. We may soon share a chronostratified planet where some live hundreds of years ahead of those still stuck in the 1900s.

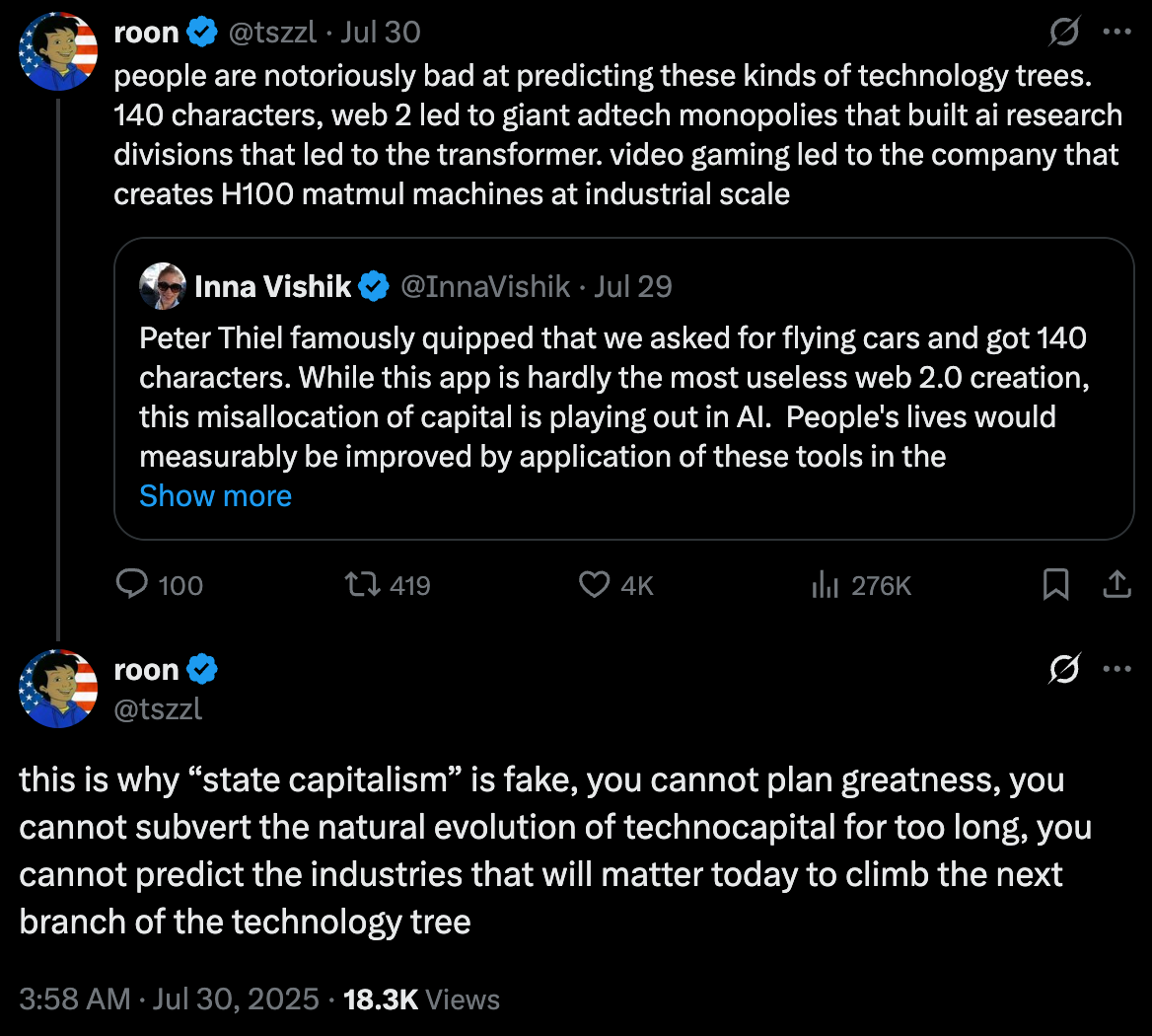

And so I am left here, pacing around my room, thinking about what will happen to civilization as we know it. As a humble market participant I have learned to respect the sometimes unintelligible magnificence of the complex systems that have emerged. The people that used to complain humanity’s top talent was being wasted on adtech and financial markets have fallen silent now as we race toward AGI. For the human observer, the complexity of the system and the progression of the tech tree has become too intricate to fully understand, much less to steer.

And yet I see politico-economic systems that reward technocapital or raw power as nothing more than weighted utility functions imposed on top of human lives. Human history shows that the unrestrained pursuit of efficiency can slide quickly into extraordinary cruelty. Our sense of fairness evolved for communities of a few hundred, not for a world where wealth and influence diverge at exponential speed all within one lifetime. The power of labor is trending down, but it still wields significant power.

In theory it could try to coordinate to slow the acceleration before inequality ignites a violent power struggle that causes a large civilizational drawdown. But coordinating the masses to understand the complexity of the situation is a difficult task. The technocapital system is so vast and opaque that most people don’t even know which levers they would need to pull, let alone coordinate to pull them together.

For now the path we are heading on is to trust that new technologies and social safety nets will adapt to cushion the impact from the post labor transition. I am skeptical on this because it seems more like complacency and ignorance than anything else.

But what do I know? I am but a single ant recently freed from labor that is spending his days marveling at the complexity of the colony we have created. For now I am still trying to better understand what is before I can say what ought to be.

What do you think should be done?

I’ll keep unpacking the politico-economic machine in future articles. If these ideas spark reactions, critiques, or counter-examples, I’d love to talk. Fresh perspectives and new tokens are always welcome.

Aaron Bastani. Fully Automated Luxury Communism: A Manifesto. Verso, 2019.

Mark Fisher. Capitalist Realism: Is There No Alternative? Zero Books, 2009.

Nick Land. “Meltdown.” CCRU Writings 1990–1997, 1994. http://www.ccru.net/swarm1/1_melt.htm.

Beff Jezos.” The e/acc Manifesto. Substack post, 2023.

I dug out my old copy of The Communist Manifesto. You're right that Marks & Engels merely create an aesthetic, but not a substantive replacement for capitalism.

The authors begin by stating "The history of all hitherto existing society is the history of class struggles" and conclude their manifesto by saying that the Communists "openly declare that their ends can be attained only by the forcible overthrow of all existing social conditions. Let the ruling classes tremble at a Communist revolution. The proletarians have nothing to lose but their chains. They have a world to win. Workingmen of all countries, unite!"

They wish to bring about their revolution by the means of ten proposed principles. Which include: abolition of private property, abolition of inheritance, centralization of credit in the hands of the state, and more.

Before we can even consider these, earlier in the manifesto they claim that "the condition for capital is wage-labor. Wage-labor rests exclusively on competition between the laborers." But with AI, the value of wage-labor is decreasing. When the proletariat are no longer the base/foundation of the capitalist machine, they're stripped of all their political power.

This got me thinking today: what use is there for a redundant class of people that do not, and cannot, meaningfully contribute to the accelerating techno-economy? What happens to the Malawi people that have practically zero chance of breaking out of their chronostratified environment? Well, they'll probably still exist. They just won't have the opportunity to join the upper echelons of society when socioeconomic mobility grinds to a halt. Globalism as the preeminent narrative of the 21st century---that strives to raise the tide for all boats---may disintegrate as wealthy, isolated groups of people dominate the economy and win all the money.

So the Malawi people won't go away. They'll still be there. And it's possible they keep living their lives as is. And so will I.

I've noticed that much of my confidence/self-esteem is derived from my place in my local status hierarchy. I'm better than my friends at pickleball and that makes me feel good. But being chronically online always makes me feel depressed because there is always someone displaying their life who's more impressive/richer/more successful than me. So the locally optimal solution may be to dig my head in the sand and enjoy/contribute to my local community, and the Malawi people can do the same, while we all collectively ignore the techno-elite who are busy building mega space yachts to explore the galaxy.

Great article.

What degree of socioeconomic power must one hold to transcend being a fish aware of the ebbs and flows to become a current manipulator?